Frieda Fligelman: early Montana author

How an early Montana writer succeeded at being herself

Excerpted from Notes for a Novel: The Selected Poems of Frieda Fligelman, edited by Alexandra Swaney and Rick Newby (Helena: Drumlummon Institute, 2009)

The Queen of Social Logic: The Life and Writing of Frieda Fligelman

Alexandra Swaney

The life of Frieda Fligelman is a cautionary and exemplary tale of a brilliant twentieth-century woman who struggled to be taken seriously as a thinker. After receiving an extraordinary education, she couldn’t or wouldn’t fit into the academic establishments where she might have found a home. She was a woman who didn’t marry, who wouldn’t wed someone who was not a real companion, yet who felt like a failure both because she missed marrying and having children, and because her work never received the kind of recognition she hoped for.

A native Montanan who in advanced age returned to the town where she was born, after an early life of study abroad, she maintained connections with friends and scholars all over the world to combat the forces of isolation in her life. Though she couldn’t get a teaching job in a university, she envisioned and outlined linguistic sociology (now called sociolinguistics), an immensely important field of study, well before its time.

She thought and wrote widely about many issues of international policy and domestic social concern, composed over 1,200 poems in English, and a few in French, penned hundreds of letters, and self-published two sociological pamphlets, and an English translation of a 17th-century Spanish play, The Discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus.

It is an irony that Frieda, who privately struggled with feelings of loneliness, uselessness, and failure, could not really appreciate the enormous impact she had on almost anyone who ever met her.

Frieda Fligelman was, she often said with traces of both pride and irony, “famous in Helena.” Mostly for her apartments; two of them, side by side at 320 N. Warren. One she maintained as an office, the other she lived in. To step into Frieda Fligelman’s apartment—as I did as a teenager in the Helena, Montana, of the 1950s—was to come face to face with a reality that exploded the confines of what one had been led to believe was an acceptable way to live. Next to the doorbell was a small piece of black plastic tape with the word “Academe” punched into it. Directly leading in from the door was the living room, entirely inundated in paper. Books, letters, magazines, manuscripts, sheet music, menus, thousands of newspaper clippings, handwritten notes on check blanks or other tiny scraps of paper, covered every available surface, including the floor. Books, journals, and slim volumes of poems and her self-published sociological pamphlets filled the many bookcases that lined the walls. “I am never lonely,” Frieda would say. “I have with me for company the greatest minds of the last ten thousand years.” There was space in this ocean of paper for a grand piano, an organ, a small table, and a couple of chairs. A pathway through the paper on the floor led through a door to the kitchen, on the left; and from the living room to the bedroom on the right. The apartment directly next to her residence housed her office and filing cabinets. Together, they were home to the “Institute of Social Logic,” a name Frieda gave to the physical and mental territory of her lifelong love affair with language, sociology, philosophy, and culture.

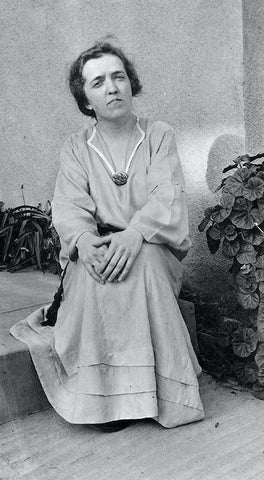

One was met at the door by a small woman of birdlike energy and intensity, blue eyes sparkling with enthusiasm for the shape, direction, and portent of her latest idea, most likely related to her dearest obsession—the value of the great things springing from the human mind: art, music, poetry, and especially, using human knowledge to better the human condition.

That idea would be expressed with a rush of breathless sentences, leaving little time for response from the enthralled listener. One moment she might offer you tea or grape juice with anise extract, and the next, sit down at the organ to improvise some “wind music.” To some—the skeptical, the uninformed or the provincial—Frieda was the quintessential community eccentric, someone to be pitied, amused by, shake one’s head over. But as she said of her expanse of unruly documents, “I didn’t degenerate into this. I am a hero for putting up with it.” The papers were an accumulation of a lifetime’s study and work, work which she valiantly pursued despite the disappointment of a lack of institutional support, the vagaries of the publishing business, and the doubts of some colleagues and acquaintances. Her whole life she hoped that a colleague would appear to help her shape these documents and scraps into the categories of thought they occupied in her mind and in her pamphlets. All printed matter was fair game for her thoughtful eye and sociological classifications; language was social environment rather than meaning.

Even seeing her on the street or at one of the innumerable public gatherings she attended in her boundless civic participation was enough for most of us to take strong notice. She usually wore a long green velvet coat with a purple velvet beret. She was very petite, not more than five feet tall, her little-old-lady cuteness beguiling. But when she spoke, she expressed directly her obvious intelligence and wit with an often outrageous candor, violating the unspoken rules of the social code for respectable women in Helena, to the great astonishment and relief of many of us.

Frieda Fligelman was born January 2, 1890, in Helena, Montana, to Herman Fligelman and his first wife, Minna Weinzweig, who died shortly after giving birth to their second daughter, Belle. One of Frieda’s favorite childhood memories was being held on her father’s shoulders to watch the parade celebrating the choice of Helena as the state’s capital city. Her father, Herman Fligelman, a Jew, had fled the pogroms of his native Rumania in 1881 when he was twenty-two years old, arriving in Boston with twenty dollars in his pocket. He quickly went to New York, got a job washing dishes, then graduated to dock work and saved enough money for passage to Minneapolis, where he worked on a streetcar line long enough to be able to buy a stock of goods.

He headed west, eventually starting, with Henry Loble and Robert Heller, the New York Store, a department store that prospered with the mining on Helena’s Last Chance Gulch. Frieda, and Belle, her younger sister, often reminisced about how much their father loved learning. They grew up consulting Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary at the dinner table and reading Shakespeare in the evenings. Under duress, Herman allowed his daughters to leave the state to get a first rate education. Frieda attended the University of Minnesota, from 1907 to 1909, then moved to the University of Wisconsin, where Belle was studying. At that time the university at Madison was a center of progressive ideas and attracted many bright young people from all over, especially New York. Both Frieda and Belle were active there in working for women’s suffrage. Belle became student body president at Madison and, after her return to Montana, worked to elect Jeanette Rankin to Congress, serving as Rankin’s secretary in Washington, D.C., after she was elected. Frieda’s article, “Early Laws of Montana for Women,” a history of women’s rights in Montana up to 1910, appeared in the Anaconda Standard of April 28, 1912, and was perhaps her first published piece.

After graduation from Wisconsin, Frieda moved to New York for graduate study in sociology, economics, and anthropology at Columbia University. She then received a Flood Social Science Fellowship to study economics at the University of California for a year, returning to New York for further classes at Columbia. At both universities, she was acquainted with prominent scholars who would later become famous in their fields.

Frieda passed her oral and written Ph.D. comprehensive exams at Columbia in 1915 with professors Giddings and Boas. During this time and in the following years, she worked as a sociologist on several short-term projects in different locations. She was research assistant for the U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations, investigating the underlying causes of labor unrest in Wisconsin (1914); Field Agent for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, director of a survey of health and housing conditions for the Fresno Red Cross, and professor of Economics and Labor Statistics at Mills College in 1920, in Oakland, California. Much of this work involved the painstaking process of collecting and analyzing statistics, which Frieda accomplished meticulously, earning high praise from her employers.

In 1920, at age 30, Frieda went abroad. Freed from working by a stipend from a trust fund set up by her father, she sailed to Europe, where she spent the next twelve years, living mostly in Paris, but also visiting Berlin, and traveling through the Mediterranean countries. She ultimately became fluent in French and German, and quite versatile in several other languages. It appears that her first destination was what is now Israel. Among her papers there is a letter of recommendation from the Palestine Economic Society, stating that she had been statistician for its office in Tel-Aviv, Jaffa, Palestine, compiling statistics on immigration from January to April, 1921.

In Paris, Frieda continued her formal studies. She attended the National School of Living Oriental Languages, taking classes with Professor Henri Labouret, a linguist and ethnologist who had lived in French colonial Africa for eighteen years. Labouret was also French Director of the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures, and editor of its journal Africa. Studying West African people and languages firsthand was a relatively rare pursuit for western scholars at that time. Sparked by her studies with Labouret, especially a class in the Fulani language of West Africa, Frieda returned to her project of proving Levy-Bruhl’s thesis—that primitive mentality was “primitive”—wrong. She conceived of a way to demonstrate that a non-western language was as complex as modern European languages, and “sufficiently well developed and constructed to adapt to the demands of twentieth century life.”

How does one prove that one language is the equal of another? Using the complete Fulani-French dictionary of Major Henri Gaden, Lexique Poular-Francais (Paris, 1914), Frieda began to reorganize the entire vocabulary of the Fulani language into categories which might be compared to similar categories in European languages. After a year of work, she discovered that the Fulani language was equal in richness and complexity to these “modern” languages in several categories, but especially in “moral vocabulary”: words, phrases, and figures of speech describing human behavior. Her conclusions were:

(A) the native African Negro language, judged by Fulani, has ample moral richness as an instrument of twentieth century ordinary daily life; (B) in its figurative expressions and its many nuances of meaning . . . it has an artistic and psychological richness which astonish everyone who has taken the trouble to investigate the subject; and . . . is such that Western languages could usefully borrow from it.3

The twenties were a heady time to be in Paris, especially for a young woman interested in ideas and culture. Frieda once told me she passed the famous modern dancer Isadora Duncan and her children in the street. One can imagine all sorts of interesting encounters that she might have had, but one in particular unleashed a different sort of writing in Frieda. She turned to poetry for expression when she found herself hopelessly in love with a married colleague.

The relationship, consummated or not, did not last long in its romantic phase, much to Frieda’s great sorrow:

Let us take comfort in another age

More learned in reason than in custom

Will scorn to waste such love,

Recoil before brutalities

Whose only purpose

Is a cloak for vanity.

How foolishly I cry,

Oh may that time

Make haste to show itself

While youth is still with me.

It is impossible—and unnecessary—to know the identity of her beloved; from inferences in the poems, he was someone with whom she worked closely, perhaps even Labouret.

How strange and fair that suddenly my friendship

Turned to Love,

Love so elemental

That I would die in joy

For one long day with you.

In the year this happened, sometime in the mid-twenties, Frieda composed half of her nearly 1,200 poems, initially writing them out by hand on small notepads. Later, when she returned to the United States, she compiled a 270-page typewritten manuscript of 930 of these poems, which she variously referred to as Notes of a Lonesome Woman, Notes for a Novel, or Warning to Youth, dedicated to “all sorts of men, in thankfulness to some, in distaste of others.” In her preface to the poems, “Explanation,” she says she has labeled these poems notes, even though they look like poetry, because

the linear form is a dress that can be worn by any idea. What is important about these pages is precisely that they are notes. Random notes are an aspect of life. They are just as legitimate a form as Alexandrines or sonnets . . . these are the notes of a lonesome woman.

She had made of her loneliness

So great an art

That now its hurt had become a melody

And she was lost in wonder

And a strange delight

At the abundant charm of her desires.

There are poems of despair and futility. Why, Frieda wondered, does nature waste so much, especially women who have love to give?

Frieda’s father died in 1932. She was in the midst of publishing her articles on Fulani, and editing the Proceedings of the 1931 Paris Congress of the International Institute for African Languages and Culture. She finally completed what was a very tedious undertaking and returned to the United States late that year. Shortly thereafter, she presented her published papers to Columbia to fulfill the requirement for the Ph.D. dissertation in sociology. But her original advisor, Professor Giddings, was no longer there, and the current chairman of the sociology department refused her work, saying, “This is not sociology, it is linguistics.” This was a rather narrow-minded approach for a sociologist even in the 1930s; there is now a well-established and vital area of study called sociolinguistics which essentially falls well within the purview Frieda had envisioned.

In 1948, she returned to Helena to care for her ailing stepmother. Feeling the pull of age and family, she decided to stay, and moved all her papers, books, and other possessions into the then-new Hustad Apartments. From that time on she was a beloved and essential citizen of Helena, Montana. A founding member of the Montana Institute of the Arts, she also belonged to the Montana Academy of Sciences, the League of Women Voters, and the American Association of University Women. She attended public meetings and cultural events and supported libraries and other cultural institutions financially. She was a lifetime member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and often traveled to attend its meetings, as well as those of the American Anthropological Association, the American Sociological Association, and the Pacific Sociological Society.

In Helena, she spent much of her time finding interesting people and introducing them to people she thought it would be helpful for them to know. She would sometimes invite total strangers to lunch. She would hire young people to come and help her with some aspect of working on her papers, or simply invite them over for talk about something they were interested in. Her sister and brother-in-law, Belle and Norman Winestine, lived just a few blocks down the street. She would often join them to go out for dinner or concerts or public meetings. This remarkable trio could change the tenor of any social situation for the better, engendering fascinating and original conversations on nearly any subject one could imagine. Norman, a graduate of Yale, had been a writer for The Nation when Belle met and married him during her stay in Washington, D.C. Their dream of making a living as progressive writers did not look as though it would support a family, and they returned to Helena, where Norman took over the management of Fligelman’s, as the New York Store came to be called. Norman’s quite wisdom and knowledge were widely respected; he was in demand as an educational speaker on many subjects and as a leader of the Jewish community in the state. After his retirement, he and Belle traveled the world extensively, but always returned to their little house on Eleventh Avenue. Belle and Norman were among the very few to attempt to keep Frieda’s loquaciousness in check occasionally when it became overwhelming to those trying to have a dialogue with her. The ideas simply flowed through her so rapidly that sometimes there wasn’t room for anything or anyone else.

There were some triumphs. One afternoon in 1978, she read her poetry to an enthusiastic overflow audience at the fledgling Second Story Cinema (now transformed into the Myrna Loy Center for the Performing Arts). Anyone who was there remembers it as an almost mythic event in Helena’s cultural history. Oldtimers and recent immigrants alike were mesmerized by Frieda, who in turn was energized by the response of the audience. We of the younger generation were startled, delighted, and amused by the sagacity and charm of this irreplaceable elder and saddened to think she might not always be with us. Arnie Malina wrote for us all when he presented Frieda with a birthday poem in one of her last years:

to Frieda Fligelman

the Queen of Social logic

a birthday poem

Lady,

who is wise enough to witness

the pattern in your clutter?

In the files which flood your living room

and fill your life with freedom,

who is wise enough to wonder

why the music had its start?

The passion that propels you

Unscheduled and severe

is the thinking of ten thousand years

run on, non-stop, right here.

Until she died at 88, January 16, 1978, Frieda was active and able to get around. She died peacefully and quickly, of a heart attack while accepting an order of groceries from the delivery boy. The Winestines asked me to go through her two apartments and determine how to disburse the remains of Frieda’s life of the mind. Three large cabinets full of files containing most of her work—a lifetime of newspaper clippings and notes on social logic, public policy, national character, and related topics—were delivered to the archives of the University of Montana library. Her sociological journal collection was sent to Books for Asia, a non-profit organization providing materials to Asian educational institutions. I kept back a filing cabinet full of biographical material and her 1,200 poems; they are now on file at the State Historical Society in Helena.

In examining such a life, in the end there remains a mystery: that one could not invent such a person were one to try to imagine her. My favorite photograph of Frieda is one taken with the Sphinx at Giza, in the early nineteen twenties. Wearing a wide brim hat, she sits astride a donkey, staring straight into the camera. Two men in burnooses stand on either side of her, holding the donkey. The print itself is striated, the emulsion scratched by the desert sand. The Sphinx looms behind the figures in the foreground, seeming to look over Frieda’s shoulder. To those who knew her, the overarching reaction to this image must be the startling accuracy of the juxtaposition of Frieda and the Sphinx.

Both emanate wisdom and enigma. Both belong to the timeless realm of divinely human knowledge and artful endeavor.

She had a substitute

For beauty that is freshness

And spring life—

She had the beauty

Of long weathered tints

On ancient monuments

Or shawls

Beauty that is chiseled in

By thought.

Frieda succeeded at life’s most challenging task: becoming completely herself.

If I Were the Queen of Sheba

I can imagine

Being the Lady Sultan

Of Arabia

With something like a harem

Full of lovers—

But they would not be slaves

No more than doctors

Are slaves to suffering patients

Or professors to eager students

Or actors and performers

To our need of re-creation.

And I would send

For Ahmed or Abdullah,

And then for Ali, Shem and Japeth,

Yakut, Iram, Boubekr, Es-Saheli,

And then exhausting memory

For names,

Call for the one who’s gentle as a hound,

And then the one who’s timid as a doe

That hardly dares to come

And lick the hand for salt;

Then I would call for him

Who loves to strut,

Thrusting his head about

Above his beautiful shoulders

Like the huge-antlered deer,

Who seems to wave a proud and graceful flag

As he runs lightly [lithely] forth

To seek his food;

And then perhaps,

The beautiful youth

With resolute noble eyes—

I would not touch him

Save to stroke his hands,

Enquire of the progress of his plans

For an attack to conquer

Some rude problem

Of the universal pain.

And all would come

With firmly glistening limbs,

Clean from cool baths

Or working in the breeze.

They would be glad to come,

As glad to go;

Returning to their fascinating art or craft

Where some fair damsel

Is their bright companion.

For they would not be slaves

Locked for my pleasure,

Waiting in anxiety

The imperious call of master.

They would come gladly

As a beautiful pause

In their beautiful work—

Our caresses

Would be the joining limbs

Of comrades creating beauty;

Our curving arms

Against the pillows

And each other

Would make designs

To rival autumn trees.

And as the leaves dropped

From our longing

And a short winter covered us

With gentle snow,

Slowly we’d melt away

Into delicious drowse of passing winter

And after half-an-hour

Spring would come again.

The birds, and singing youth

At charming tasks

Outside the windows

Would wake and call us

Not to waste in an unconsciousness

The little space of life

Which must be used to hold

So many joys.

Apologia

Do not wonder at my darting mind!

I am one who walks on crevassed ground,

Where unsuspected fissures

Continually alert the contemplated step

Arresting confidence midway in hope.

Doubts

When you persist against all evidence,

Believing you are on the tracks

of truth or love or art,

As if a master-hand were guiding you,

Is it subconscious understanding

Or only nuttiness?

Leave a comment